The World of Charles and Ray Eames

The World of Charles and Ray Eames runs at the Barbican, London until February 14. Here’s my review of the show for New Design 119.

*

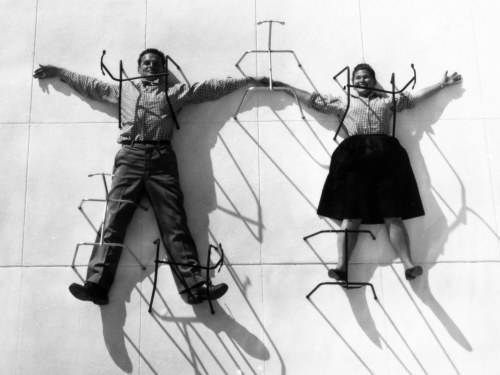

On either side of the Atlantic run parallel narratives of post-war modernism. From the blitz-bombed streets of London rose brutalism manifest in the form of the Barbican; meanwhile in the sunshine and space of California, Charles (1907-1978) and Ray Eames (1912-1988) were busy defining the stylistic sensibility of mid-century America. These two strands converge in the Barbican exhibition The World of Charles and Ray Eames, the first retrospective of the designers’ work to be held in the UK for fifteen years.

We start in dramatic fashion not with a chair or couch but a study for a glider nose cone in bent plywood. This imposing, graceful, even sculptural wooden arch is swiftly followed by a battlefield leg splint in the same material. It is a reminder that the output of the Eames Office, established in Venice, California after the newly-wed Charles and Ray relocated to the West Coast in 1941, was underpinned by the principles of industrial design and relied on testing material properties, those of plywood in particular, to structural and creative limits. The furniture pieces for which the Eameses are best known would see the application of such techniques in the domestic mileu.

Significantly, what the visitor next encounters is a cabinet containing copies of Arts & Architecture magazine with covers designed by Ray Eames. In this juxtaposition between product and visual media the exhibition, sophisticatedly curated by Catherine Ince, establishes an important crux. Namely, that the Eameses were as prolific in Letterpress as plywood. Indeed, the Eameses’ close relationship with the design media allowed them to carve a space in which to mythologize their own reputation.

There has been a recent trend for ‘World Of’ exhibitions whereby it is not only a designer’s output but the paraphernalia of their environment which is of interest – last year’s Hello, My Name is Paul Smith at the Design Museum being an example. In the case of Charles and Ray Eames such an approach is utterly justified: they embraced design celebrity and were eager that their own way of life and aesthetic taste might be a model for modern America.

Within the pages of Arts & Architecture (then under the editorship of John Entenza), the Eameses documented the design and build of the Case Study Houses 8 and 9 in Pacific Palisades – companion buildings which were occupied by Charles and Ray (8) and their long-time collaborator, the Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen (9). Architectural models of both of the houses, enormously influential in post-war building design, as well as photography of the Eameses enjoying domestic life shot for mainstream magazines are among the 380 works collected across the two floors of the Barbican Art Gallery.

Of those 380 pieces it is, of course, the furniture that will sell the tickets. And understandably so, for what a remarkable oeuvre the Eames Office produced in its four decades of activity. The plywood seats of the 1940s show the Eameses experimenting with technique and form. At this point the potential for the mass manufacture of furniture was beginning to be realised and its interesting to note in the exhibition signage a surprisingly utilitarian mantra attributed to Charles that his practice was about “getting the best to the greatest number for the least.”

This is truly Arcadia for the design enthusiast. A particular stand out piece is the perfect simplicity of the 1946 LCW (Lounge Wood Chair) – a two-piece low-seated plywood chair that Time magazine named ‘the chair of the 20th century’.

The pieces narrate the evolving relationship between the Eames Office and the furniture manufacturer Herman Miller as well as, in places, revealing a more personal touches. We have a lounge armchair designed for film director and friend of the Eameses Billy Wilder – its low base is said to have been designed to make sure Wilder would not fall out of his chair if he got overexcited whilst watching his beloved televised sports. Meanwhile, bucket chairs from the Eameses’ house have been charmingly customized with cat drawings by illustrator Saul Steinberg.

Whilst many will access the Eameses through the furniture, their work stretches broadly across graphic design, painting, photography, film making, and the built environment. “The Eames Office was an intensely interesting and busy practice that used any tools to communicate any subject of interest to Charles and Ray Eames,” explains curator Catherine Ince. “You can see that visual communication was central to the Eameses’ practice: Charles was a prolific photographer, Ray possessed a tremendous eye for art direction.”

With America on the cusp of the ‘information age’, the successful shaping and transmission of a message was a preoccupation of Charles Eames in particular. Nowhere is this more evident that in the Eames Office’s work for IBM – the subject of a mid-exhibition digression on which is its worth pausing.

The computer company IBM commissioned the Eames Office to design its pavilion for the 1964/65 New York World’s Fair. The project was the Office’s most significant undertaking to date and involved not only defining the pavilion’s architecture but also crafting the multimedia message that IBM would present to show-goers.

At the heart of the concept was the ‘Ovoid Theater’, essentially an egg-shaped pod supported some 53 feet in the air. It was large enough to seat over 400 guests and housed 22 screens of various sizes, which displayed ‘Think’ a film created by the Eames that explored the relationship between computer science and everyday problem solving.

Visitors to the Barbican exhibition can experience a version of ‘Think (albeit scaled-down from the original) with film and static images across seven screens. The Eameses’ vision of the future is served with a slice of All American apple pie: there’s the football coach chalking up plays as a version of ‘symbol and reality’ that is likened to the wind-tunnel testing of a fighter jet; a well-to-do housewife attempting to organise a dinner party seating plan is a corollary to computer modelling; and the major benefit of accurate weather forecasting? To predict the number of hot dogs that will be sold at a baseball game.

What feels initially like a digression introduces a theme that underpins the exhibition: that the Eameses are products and authors of the American Dream. Whether it is sports or social climbing, furniture or domestic architecture, what is at stake here is progress and aspiration. It is at this point one becomes aware of a key piece which has not yet been encountered.

I refer, of course, of the Eames lounger. That recognisable combination of aluminium, rosewood ply, and leather that together with its companion ottoman speaks of executive America. It confronts the visitor as they begin the exhibition’s upstairs’ circuit. Majestically lit, organic yet imposing, the lounger demands attention. Can there be a more iconic work of furniture design.

The example secured by the Barbican shows a slight weathering of the ottoman’s leather. One cannot help but speculate as to the heels that caused such erosion – one imagines the Brooks Brothers suit, the taste of whiskey, the whiff of cigar smoke. The lounger, one of the first pieces design by Charles and Ray Eames explicitly for the high-end market, is in its own way a symbol of American corporate power.

The lounger and ottoman were released by the Herman Miller company in 1956, but not after many years of experimental development. The studies in the material capabilities of plywood and the optimal organisation of seat design through the 1940s appear to move towards this moment. Beneath the Californian smiles there was hard graft and compulsive attention to detail. As such, perhaps the lounger is the arch articulation of one of Charles’ favourite sayings, borrowed from the movie business: “Never let the blood show.”

The exhibition design by the London-based 6a architects is understated and coherent. The journey through the two storey space is essentially chronological with much opportunity afforded along the way to dwell of digress as attention demands. Quite rightly it is the furniture works that are the hero pieces, the narrative markers in the story of the Eames Office, with the multimedia visual communication output functioning as an ongoing dialogue.

One of the final exhibits is the reproduction of an extraordinary film, a question an answer sessions between Madame L. Amic and Charles Eames originally recorded for the Louvre’s 1969 exhibition ‘What is Design?’. Eames’ responses are remarkable in their succinctness – he is happy to offer one or two word answers not out of belligerence but out of confidence that he has said all that is required. Asked the titular question – what is design? – he responds elegantly: “a plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose.”

Eames’ precisely worded understanding of design is followed to the letter in the execution of the Barbican show. This is exactly what an exhibition of design ought to be. In tackling the work and careers of two of the discipline’s most significant practitioners The World of Charles and Ray Eames is simultaneously obsessively detailed and pleasingly broad. The focus on process in the Eameses’ modes of expression, whether that be furniture design, visual communications or film, invites the visitor to explore broader questions around the cultural and commercial function of design.